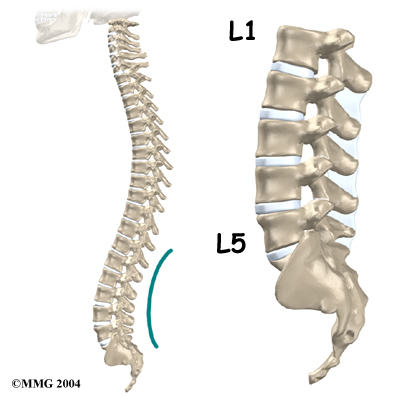

In the last blog, I discussed disc herniation. Today, I’d like to go a little bit more in depth on this subject. The most common place to herniate a disc is at the L5, which you can see on the image below.

Image via Orthopod

The L5 level actually refers to two discs:

* The L5-S1, which is between the 5th lumbar vertebra and the tail bone – You may have a L5-S1 disc herniation if you sense weakness when standing on your toes accompanied by pain in the foot.

* The L4-L5, which is between the 4th and the 5th lumbar vertebrae – You may have a L4-L5 disc herniation if you have weakness when raising your big toe accompanied by pain along the top of the foot.

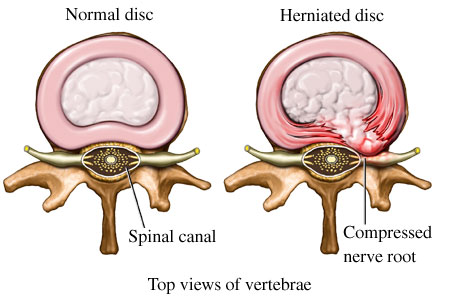

You’ve probably heard that it is possible to have a herniated disc and not know it. This is because, most of the time, only a herniation at a very specific spot on the disc has the capability of putting pressure on the nerve. Try to imagine looking down at a disc from a birds-eye view (*see image below). From this angle, it is round like the face of a clock. The spine would be at the 6 o’clock mark. If the herniation is in the 4-5 or 7-8 o’clock areas, it is likely to be pressing on a nerve as it is getting ready to exit the spinal canal just below. As you can probably imagine, this pressure on the nerve can be quite painful. If the herniation occurs in other areas, you may not experience symptoms such as pain, and there really isn’t enough disc material to have an affect if the herniation occurs at the 6 o’clock position. For that reason, most of the disc herniations I see at River Ridge Chiropractic are in the 4-5 and 7-8 o’clock positions.

Image via WebMD

So how exactly does an L5 disc herniation occur?

When the stomach side of the of the disc, called the anterior side, is compressed while sitting or bending forward, the nucleus of the disc gets pressed against the back-side of the disc. If that part of the membrane is stretched too thin, it can rupture. The nucleus can then move into the spinal canal, putting pressure on the nerve, as we discussed above. You may be asking, “How does the outer part of the disc become thin or weakened?” Sometimes, it’s from general wear and tear, either from too much sitting or too much lifting. Sometimes, it’s a traumatic injury from lifting something heavy improperly (failing to lift with the legs). In other cases, the disc may degenerating because of genetic factors. In all of these scenarios, something called Degenerative Disc Disease (DDD) may be partially to blame. In next week’s blog, I’ll discuss DDD in more detail.

Dr. Bart